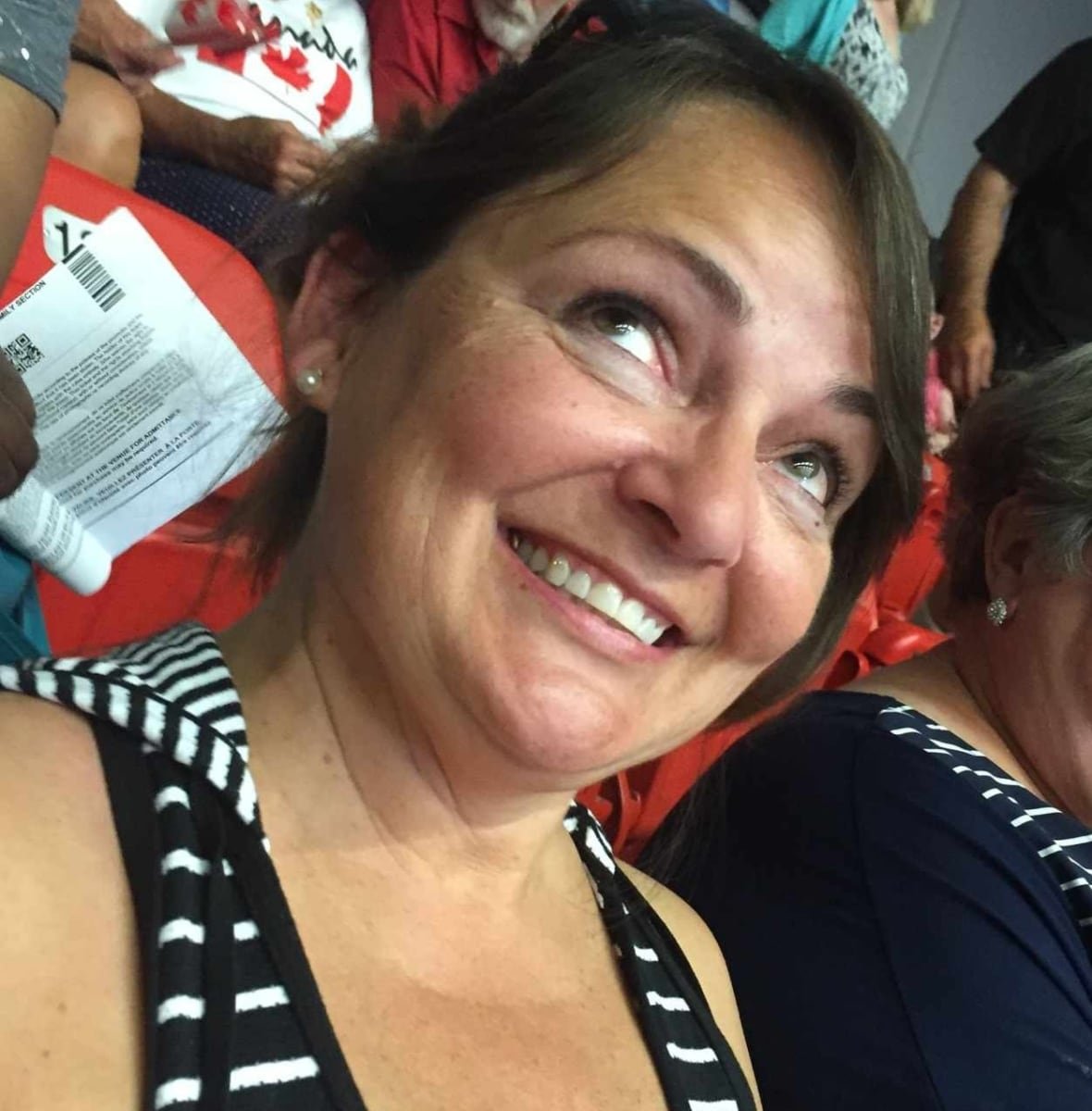

The daughters of a woman who was killed in Nova Scotia twelve days ago by her husband before he killed himself are calling on the RCMP for more transparency around domestic violence, alleging the force is covering up what happened because their mother’s husband was a retired Mountie.

Tara Graham, 41, and Ashley Whitten, 38, say their mother, Brenda Tatlock-Burke, 59, was in a toxic and controlling relationship with their stepfather, Mike Burke, for more than 30 years and had told them she was planning to leave him just two days before she was killed.

The women are upset about the information — or lack thereof — that the RCMP have released about the case, saying it has led to a false narrative about what occurred and that they want their mother’s story known publicly to raise awareness of domestic violence.

“I just want [the RCMP] to acknowledge the facts and the truth of what the situation was,” said Graham during an interview at her home in Cochrane, Alta.

The RCMP did not immediately label Tatlock-Burke’s death a case of domestic violence and won’t confirm it involved a retired officer. Only after CBC News told the RCMP the family was upset the force had not done so, it released a statement confirming the investigation shows this case to be an incident of intimate partner violence.

The RCMP declined an interview request, but in a statement said, “we’re unable to confirm or disclose any individual’s past employment status unless it’s to advance an investigation.”

On Nov. 8, more than a week after the family spoke out, the RCMP issued a news release confirming the incident involved a retired member of the force.

In a case in Ottawa last week, where a woman was stabbed to death in a park by a man she knew, the Ottawa Police Service publicly stated it was a case of femicide within 24 hours.

Daughters determined to share mother’s story

The RCMP first issued a news release on the evening of Oct. 18, saying it had received a request that morning to do a wellbeing check on two people at a home in Enfield, N.S., at around 10:45 a.m.

The release said officers found the remains of two adults deceased inside the residence, that they were known to each other and that their deaths were being treated as suspicious.

Four days later, on Oct. 22, the RCMP issued an update saying they had determined the woman had died as a result of homicide and the man as a result of self-inflicted injuries.

This release said that “in consideration of the Privacy Act and out of respect for the families,” the force would not be releasing any further information.

Graham and Whitten say they were never asked whether they wanted information released.

This is what they want people to know.

At the end of August, Tatlock-Burke went to Alberta to spend nearly two months with her daughters.

She told them both that she was planning to leave her husband upon her return to Nova Scotia. They helped her change her name on social media to “Brenda Tatlock.”

Whitten brought her to the airport on Oct. 16.

“When I hugged her at the airport, I asked her if she thought he would ever hurt her and she said ‘no,'” Whitten said during a phone interview from her home in Fort McMurray.

Two days later, she was dead.

Graham says her brother, who lives in Nova Scotia, told her he received a text from Burke that morning telling him to call the police.

She said the medical examiner told her Tatlock-Burke died from a single gunshot wound.

Both daughters say their stepfather did not have a diagnosis of PTSD. They do not believe their stepfather had ever hurt their mother physically prior to Oct. 18.

“I want people to know that even though you don’t see a bruise, it could happen,” said Whitten.

Both Graham and Whitten agree it is important for the RCMP to tell the public their stepfather was a retired officer.

“I just think that to save face for the RCMP, it would be better fitted to their agenda if that information didn’t come out,” said Whitten. Graham said her mother had a false sense of security because her partner was an RCMP officer.

“When you’re protecting people who have that kind of authority or stature in society, you’re making it really hard for people that are in that position to leave because they think that it’s only happening to them,” she said.

Transparency needed, says advocate

Meghan Hansford, who has a Ph.D in domestic violence intervention and prevention, says the Ottawa case is a step forward. She says historically authorities have not named intimate partner violence.

“There is kind of a conspiracy of silence that kind of keeps perpetuating when we don’t call it what it is,” said Hansford, housing support program manager at Adsum for Women and Children, a shelter in Halifax.

The daughter of Brenda Tatloc-Burke, a Nova Scotia woman murdered two weeks ago by her husband Mike Burke, is calling on the RCMP for more transparency in the case. She says Burke, who was found dead by suicide at the scene, was a retired RCMP officer but so far the force has not confirmed that.

She’s also calling on the RCMP to be transparent when one of their retired members is involved.

She says when the partner has a background in law enforcement, victims are more vulnerable because their partners have access to weapons, leaving can require speaking out against a respected member of the community, and their partner likely knows the locations of shelters and safe spaces.

“It’s almost an insurmountable hill for people to be able to to leave and to escape and to be safe,” she said.

Tatlock-Burke’s daughters say they want her to be remembered not just for the terrible way she died, but as a creative, outgoing, person who loved to sing, an entertainer who loved to make people laugh.

For anyone affected by family or intimate partner violence, there is support available through crisis lines and local support services. If you’re in immediate danger or fear for your safety or that of others around you, please call 911.

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to get help:

-

Canada’s Suicide Crisis Helpline: Call or text 988.

-

Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868. Text 686868. Live chat counselling on the website.

-

Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention: Find a 24-hour crisis centre.

-

This guide from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health outlines how to talk about suicide with someone you’re worried about.