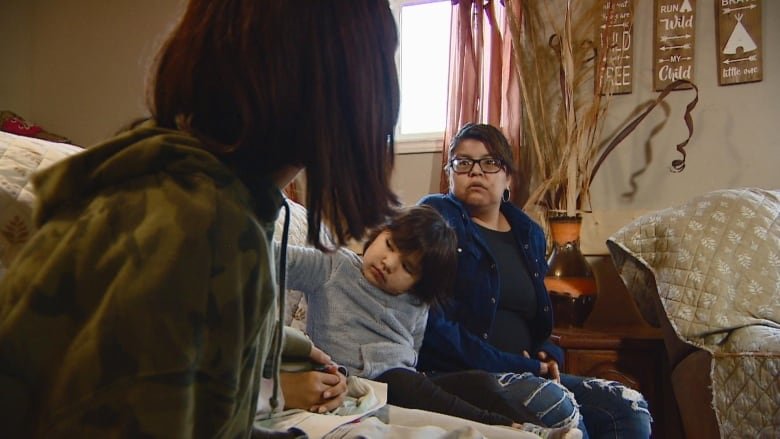

Kristen Whitehead picks up a few crumbs from the couch and some candy sprinkled on the living room carpet of her Nipawin, Sask., home, presumably left behind by one of her seven kids. She does it without complaint. It’s taken years to reach the point where she can live in a home with her children again.

They were living together in 2018 — the year she became addicted to crystal meth.

About two years later, she was evicted when her addiction led to missed bill payments and, ultimately, to her kids being taken into her family’s care.

Between then and now, Whitehead surfed from couch to couch at the homes of family members. She considered herself homeless because it wasn’t permanent housing where she could stay with her kids.

“I didn’t belong anywhere — mostly walking around town trying to think of how to get to where I am now,” she told CBC, sitting in her home near her four-year-old daughter, who was plopped on the couch with a Popsicle.

“I wanted to focus on getting my kids back and my family back.”

Her situation made her part of what’s described as the “hidden homeless” population — people who aren’t necessarily living on the street, but have no permanent address.

Nipawin is one of a dozen smaller communities tallying their homeless populations — including the “invisible homeless” population — with funding from the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan. The goal is to show the problem exists in these places, then use that evidence to get more resources to help.

Last October, the provincial government announced its “approach to homelessness” plan, which included millions in provincial funding toward 155 new supportive housing units, 120 permanent emergency shelter spaces and 30 complex-needs emergency shelter spaces.

All of the supportive housing units and complex-needs beds funded through the plan will be located in Regina and Saskatoon. Most of the 120 shelter spaces are designated for those cities and Prince Albert.

The three cities are set to get 95 enhanced emergency shelter spaces divided between them — open around the clock, offering three meals a day and wraparound supports.

The remaining basic shelter spaces, open for limited times with limited meal services and external referrals to support agencies, are set for Meadow Lake and La Ronge, which will each get five spaces, and Moose Jaw, which will get 15, according to the province.

Leaders from Nipawin and Moose Jaw organizations who spoke with CBC say homelessness has grown, driven by a lack of affordable housing and support for addictions and mental health.

Whitehead said her kids called her while she was in the throes of addiction, pushing her to find housing so they could live together again.

She sobered up two years ago. She went to social services, which brought her to the Nipawin Oasis Community Centre Co-operative, where she now works, for help.

Whitehead moved into one of seven supportive housing homes managed by the centre. According to its staff, it’s the only organization with a housing and homelessness program that offers housing and additional support.

How bad is homelessness here?

The Nipawin Oasis centre spent 24 hours last week, beginning Tuesday morning, trying to determine how many people are unhoused in the town — about 120 kilometres northeast of Prince Albert — using a point-in-time count, a community-level effort meant as a snapshot of both sheltered and unsheltered homelessness.

Every couple of years, the federal government compiles national data from point-in-time counts in major cities to learn about homelessness in each province. But those counts typically don’t include smaller Saskatchewan communities.

Alongside Nipawin, the Métis Nation–Saskatchewan is funding counts in 12 communities as small as Beauval (population 685) and as large as Moose Jaw (population 33,665 in the latest census).

About $250,000 from the federal government’s homelessness strategy was channelled through MN-S to the communities.

“I believe there is no better way of measuring homelessness than physically going out there and counting homelessness at a given time,” said Mathieu Gaudet, the acting director of housing and homelessness for the MN-S.

“Is it going to capture everything? No, but I don’t know of any better tools.”

This is the second time Moose Jaw has had a count through Square One Community, which works to provide housing in the city. Its preliminary data found 118 unhoused people — 74 were surveyed and 44 others appeared to be homeless and were either sleeping or refused to be surveyed.

In 2023, Square One held an independent count, surveying 26 people and observing another 32. Part of the increase this year was because of how Square One conducted the count, according to organization co-ordinator Maxton Eckstein, but the volunteers who did the count both years say they’re seeing worsening homelessness affecting a wider demographic.

“It is very concerning, especially with a Saskatchewan winter on the way and seeing this increase of people needing supports. It has me very concerned, and I think it should have the community very concerned as well,” Eckstein said.

LISTEN | A year ago, Saskatoon Morning spoke with people experiencing homelessness:

Host Leisha Grebinski speaks with Saskatoon Morning’s Danny Kerslake who visited Edwards Manor, where people with “complex needs” can find home.

Recently, Riverside Mission in Moose Jaw closed its 10-bed emergency shelter, leaving the 15-bed Willow Lodge, run by the John Howard Society, as the only emergency shelter in the city.

Eckstein said that while Moose Jaw is near the size of Prince Albert, it’s considered rural and remote under the federal model, which means it has access to a pool of funding spread between a larger number of communities.

“We’re on a cliff’s edge right now. With these numbers surging and people needing services right now we have an opportunity, at this point, to provide supports for people and start turning around people’s lives,” he said, specifically speaking about supportive housing.

Square One is working on getting access to a 15-suite location for supportive housing and is talking with the provincial government in hopes of nailing down core funding to ensure it can open to full capacity, he said.

“If those services don’t come, we’re going to see some very serious detrimental effects in this city.”

At the Oasis

For the Nipawin Oasis, the point-in-time count is a chance to gather official numbers that can be used to advocate for more services.

“We do have issues here, the same as what they’re struggling with in the cities, but we are not equipped with the resources to even make a dent in the problems,” said Leigh Landry, the housing and homeless co-ordinator for Nipawin Oasis. She hopes the numbers from the count inform people in power of the extent of the problem.

“We just do not have the proper supports in the community to send people to, so we do what we can here.”

She said the Oasis helps people find housing, sort through eviction appeals and get identification to enter programs like the Saskatchewan income support program, though she complained about that program’s effectiveness, as have other housing advocates.

The Oasis shared data from its preliminary count, which surveyed 99 people.

With a population of 4,570, that would mean about two of every 100 people in Nipawin are unhoused.

Landry knows the people and the area. She suspects there could have been another 30 people surveyed, but they couldn’t be found.

Of those surveyed, 84 are considered part of the hidden homeless population, while 15 are sleeping in tents, vehicles or on the street. That does not include the 41 children who are also couch surfing, according to the Nipawin Oasis.

Unlike larger communities and cities, where people may be sleeping on sidewalks and benches in the city’s core, Landry said people in Nipawin can be “tucked away” in overcrowded homes or in tents somewhere off in the bush, invisible to the public and to officers who might force them to move.

Of the approximately 69 families the organization helped in August, 22 are experiencing homelessness, Landry said.

“It’s not just affecting a certain group or class of people — we’re talking about families with kids,” she said.

The Nipawin Oasis’s interior looks more like a grandmother’s cabin than a community centre. In the kitchen, two women are preparing food, with a plate of cinnamon rolls on one table and fruits, granola bars and a bag stacked with bannock on another.

As Landry walks around the building, she’s stopped by someone who walks through the door. Landry hands him a donated jacket. In only a moment he settles it on his shoulders, decides it’s a good fit and walks out, no questions asked.

Jackets are a commodity in Nipawin, given there are no emergency warming shelters. If someone is unhoused in the winter, Oasis tries to help people work through the alternatives: staying with someone they know, even providing a food bag as a way to barter; checking in with shelters in the larger cities a couple hours’ drive south, which can be full; or booking a hotel room for them.

But Landry says the centre does not have enough disposable income to book hotels often. It does not receive core funding and depends on government grants.

The Oasis nearly sold its building and shut down in 2012 because of financial troubles. Last year, it raised funds to pay its property tax, according to staff, though its executive director said it’s in good financial standing now.

While answering more questions, Landry paused in response to incoherent yelling upstairs and abruptly ran toward it. It was mid-afternoon, and she had another 17 hours on what she said would be a 20-hour shift — one significantly extended to manage the point-in-time count.

Where to stay?

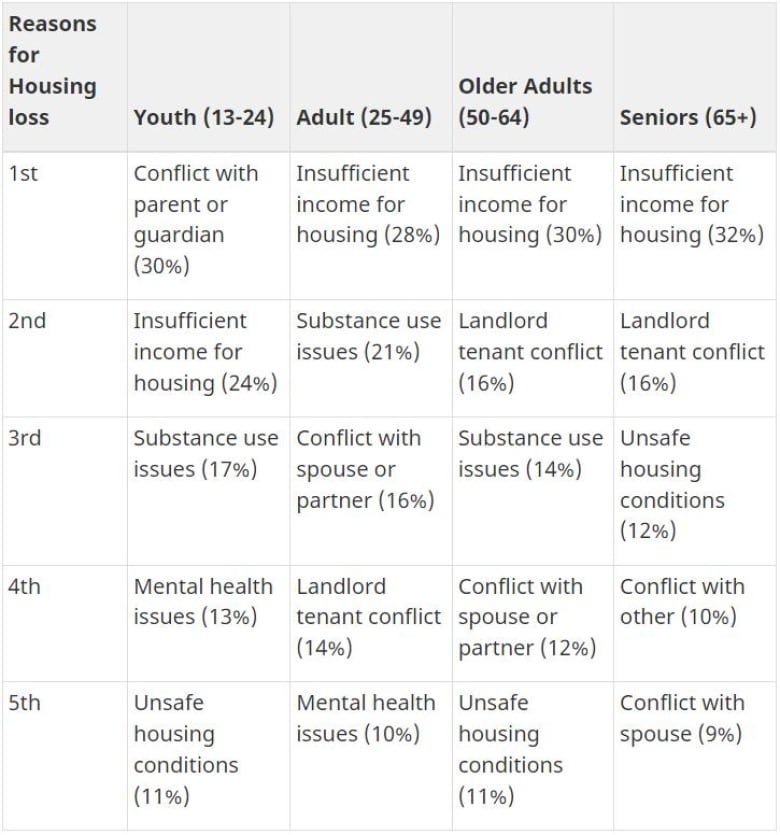

National data from the most recent point-in-time count, which concluded in December 2022, said the top reason for housing loss in adults age 25 to 49 was insufficient income (28 per cent), followed by substance use issues (21 per cent).

For youth age 13 to 24, the largest cause was a conflict with a parent or guardian (30 per cent) followed by insufficient housing income (24 per cent).

Ida Bird, a 25-year-old in Nipawin, said her addiction and housing issues are preventing her from being reunited with her five-year-old daughter, who stays with Bird’s mother and sister. Bird visits her, but doesn’t stay because of her addiction issues.

In an ideal world, she could return to school, become a chef and live with her daughter.

She’s been staying in a home for two or three months, but has been in and out of homelessness since about 2020, she said. The home has lots of foot traffic — people looking to visit or for a place to stay for the night, she said. It’s a mix of family, friends and random people.

She had previously stayed at her aunt’s place, which was similar but felt more safe, she said.

The alternative is staying in abandoned homes or outdoors, which is especially perilous in the winter.

Last year, 15 people died in the province from weather exposure, according to the Saskatchewan Coroners Service, though that number does not differentiate between deaths related to heat or cold. Of those deaths, 10 involved drugs or alcohol and one involved a person whose residence was “unknown.”

Bird said she has never had to sleep outside, but those who do have to build what she described as a miniature sweat lodge, with a small fire and layers of winter clothes and blankets.

In the home where she’s staying now, “I do tend to sometimes worry about my own safety, which is when I don’t sleep, so I can make sure nothing gets stolen, no one gets hurt,” she said.

“You never know what anyone will do.”