I asked a group of film-lovers a question recently: what’s a movie you adored but never, ever want to watch again?

The responses, and the reasoning behind them, were fairly unsurprising. Requiem for a Dream, Come and See, Midsommar: powerful stories whose exploration of the extremes of human cruelty and suffering leave you strung out, squirming, taut and exhausted. And, most importantly, with no particular itch to return.

With Hard Truths, we may have another title for the pile. It’s a surprising addition given the subject matter — no war crimes, flyblown corpses or sewn-up bear carcasses are to be found in writer-director Mike Leigh’s newest effort. Instead, it’s an impressionistic portrait of scattered lives, a tragicomedy made from the perspective of various members of a Black family slowly rotting in London.

There’s Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), the stay-at-home adult son whose hidden life only rarely opens to show glimpses of repressed passion (a preoccupation with planes, pilots and all things flying) and suppressed rage (a middle finger pointed at a closed door).

There’s the father, Curtley (David Webber), a sad-eyed professional mover who spends more time being talked at by his surrogate work-son than talking with his actual offspring. There’s the gregarious but grieving aunt; the bubbly cousin stymied at work; and our central character, the mother, Pansy (Marianne Jean-Baptiste).

Pansy is immured in a fortress of bitterness she can’t help but reinforce. She’s a scowling serial complainer, the kind of dependably cruel customer who prompts senior retail workers to tap new hires on the shoulder and say, “Don’t worry, I’ll take this one.”

Difficult character study

Pansy complains about never being invited to events, and complains when she’s asked to go. She furiously scrubs and cleans every inch of her home and body, then sleeps through the day out of exhaustion brought on by myriad non-specific health concerns.

She screams in wild terror when woken, reared-up and walleyed like a cornered animal — though why she would feel cornered in her aggressively beige, suburban home isn’t immediately clear. It’s not until she screams at a similarly cornered animal in her backyard — a terrified fox looking for a way out of the trap it willingly walked into — that the film’s conceit starts to crystallize. In both cases, they are backing away from Pansy’s husband.

As a character study, Hard Truths is painfully good. It might be the most accurate portrayal of borderline personality disorder ever put on screen, and could become as well-known for depicting that condition as No Country for Old Men is for representing psychopathy. In fact, Hard Truths ruminates so incessantly and incisively on the type of person whose irrational fear of abandonment leads to emotional explosions that it could find use as a shorthand. Instead of lengthy pamphlets or uncomfortable conversations, worried relatives could ask: “Just curious, have you seen Hard Truths?”

If it sounds sparse in terms of story, that’s because it is. Other than Pansy and her sister planning and re-planning a visit to their mother’s grave, Hard Truths is hard up for a plot. It instead rests on the power of Jean-Baptiste’s performance, and the authenticity of the backgrounds she and her surrounding cast represent.

The first, as a woman trapped in a domestic nightmare of her own making, is relentlessly compelling. Jean-Baptiste puts in the tireless work of bringing Pansy to life; not only as a curmudgeon, but one so ensnared by her patterns she can’t pull back from them — even as she watches them destroy her.

It’s almost entirely through Jean-Baptiste’s impeccable control of the smallest aspects of her expressions that we see she is both terrified and confused by her impulses. Pansy will wound her family with cutting vitriol, and then look so quietly confused and panicked afterwards you wonder if she’d just returned from an out-of-body experience.

Webber is masterful in this regard as well — not since Casey Affleck in Manchester by the Sea has an actor made drinking a beer so heartbreaking. But it is Leigh’s focus on Pansy that holds every other sadness together.

He’s painstakingly even-handed in that handling. Leigh goes to great lengths to neither let Pansy off the hook nor indict her. Something like the truthful but clumsily direct Dolores Claiborne rested its thematic reveal on choosing which of the three persecuted women had correctly handled their lot in life. In it, the officious Vera Donovan delivers the moral: “Sometimes, being a bitch is all a woman has to hang onto.”

That is exactly what Pansy is holding onto. But Hard Truths does not say whether she’s right or wrong to do so. The film only shows why she uses that attitude to endure a smothering maternal role she only accepted out of fear — and how it is (figuratively) killing those around her and (quite literally) killing her.

Hard truths, right?

Universal truths

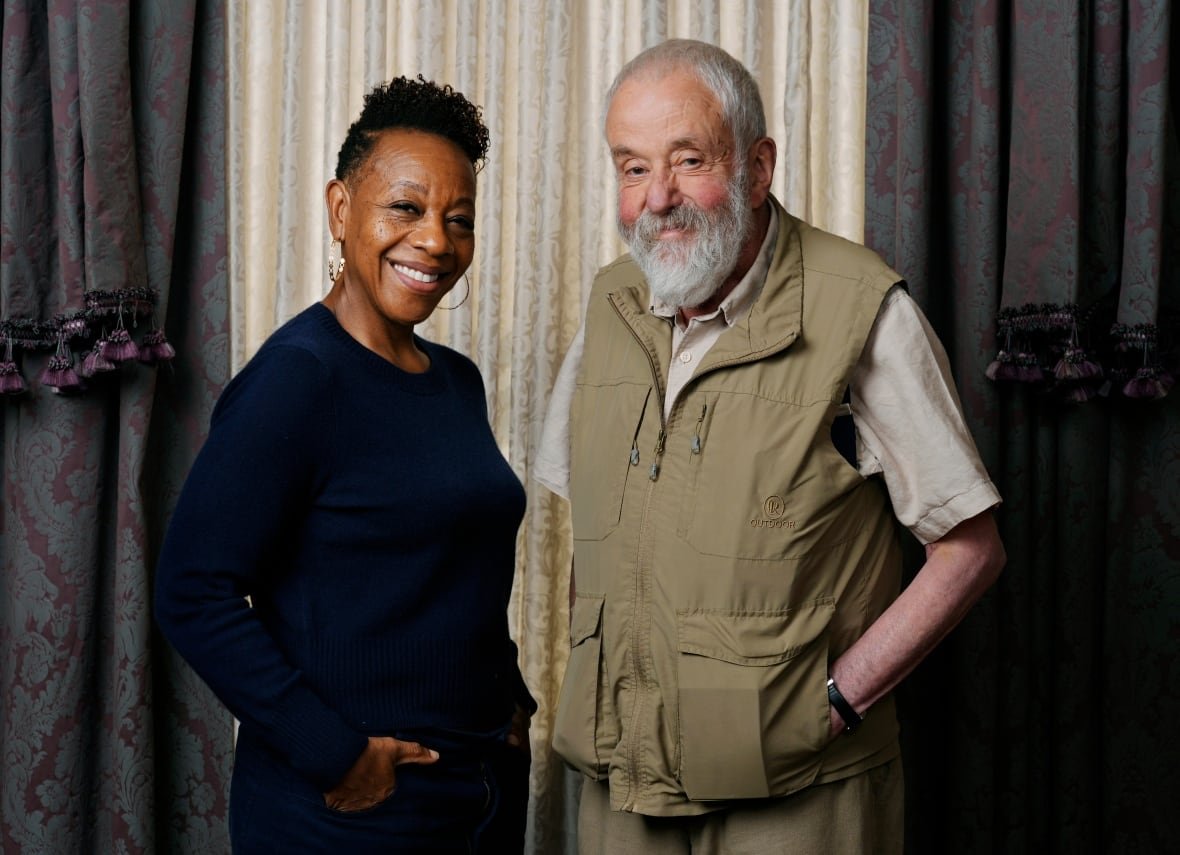

The other background Pansy represents (bluntly, as a Black person) is shared by nearly every single cast member — which might seem odd given Leigh’s own background. But like his other films, Leigh (who is white) built the dialogue and specifics of the film from actor-led workshops. Here, the cultural legitimacy serves the additional purpose of deflecting claims of appropriation. Like Waves, the Black-excellence movie helmed by white writer-director Trey Edward Shults, Hard Truths‘ implied defence is that its Black actors had a direct hand in formulating the specifics.

As the Times in Britain put it to Leigh in a recent interview, there have been complaints: is it racist for Leigh to tell a story that isn’t his? And shouldn’t his actors get writing credits if they’re the ones coming up with so much of that world?

Responding to the former, Leigh said the accusation itself was offensive and racist. His argument seems to fly in the face of the Anna Karenina principle: instead of all happy families being alike, to Leigh, all unhappy families share a universally recognizable core.

And Leigh has hit on something true about humanity, instead of just one slice of it. His careening collage of Desperate Living-esque, well, desperate living could have been cut-and-pasted between scenes of Todd Solondz’s Happiness (just lay some teeth-sucking on top).

Because Hard Truths believes that for all of our beautiful specifics, we all know a Pansy. And under the skin, their bitterest fears are the same. This kind of “I don’t see colour” mentality would be exhausting if Hard Truths weren’t right about one fact: we’re all desperate in the same way.

As for the credits argument, it’s partly a red herring. A huge part of this film’s power is in the actor-derived dialogue, and those actors should have recognition for it. But writing the general story separate from dialogue and scene specifics was an integral part of Hollywood until The Brave One won the since-abolished Oscar for best story in 1956.

And the concept shines just as brightly, despite the “comedy” part of tragicomedy being almost impossible to detect here. Instead, the film’s skin-crawling explication of emotional self-immolation basically amounts to a horror movie, or something closer to medicine. Again, the “hard truth” (get it?) is that there can be an enormous cost to self-preservation.

And in the immortal words of of those Buckley’s ads, it tastes awful…. and it works.